Did you live in Red Road flats in the late 1960s or 1970s? Do you have ‘mulitstorey memories’ you would like to share?

We’d love to hear from you. Please fill out our short online questionnaire

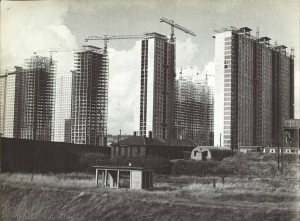

Source: ©Virtual Mitchell, C3955 Red Road n.d.

Red Road has become a symbol of Glasgow’s post-war high rise building drive and the perceived ‘failure’ of the ‘multis’ as an experiment in social housing.

Today, Sunday 11 October, the remaining flats were partly demolished (two blocks were demolished in 2013). It would seem that the demolition today didn’t entirely go to plan. This controversy follows Glasgow City Council’s plan to blow the flats down as part of the Commonwealth Games opening ceremony last year (abandoned due to public outcry).

Here’s a link to the demolition on the BBC news

Red Road polarises opinion. To some it was an eye sore, was always a ‘no go’ area, they’re glad to see it gone. To others it was home, this is where they grew up, this is where they raised their children. They were ‘good flats’. For many the demolition has brought mixed emotions (see responses to a recent article in The Guardian).

Early Years

Source: ©Virtual Mitchell C4400 View looking south before development

Designed by architect Sam Bunton using steel frames, this was his attempt at importing the New York Skyscraper to Glasgow (Glendinning, Tower Block, p. 232). Red Road was controversial from the beginning. It was constructed by Glasgow Corporation’s Direct Labour force which had little experience of ‘building high’. Work began in 1963 and was plagued by delays and the build went over time and budget.

The early critics

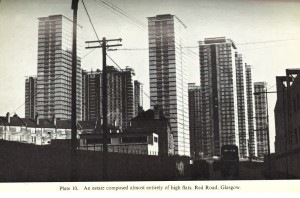

Source: Hurtwood, Planning for Play, 1968, p. 14

In 1969 when the blocks were completed they were the highest in Europe and housed approximately 4,700 people. Architectural critics at the time were unimpressed with the ‘cynical population-containers’ (Colin McWilliam, 1965) and the scheme’s ‘nightmare sublimity’ (Nicholas Taylor 1967) (Glendinning, Towerblock, 1994, p. 315). Lady Allen of Hurtwood, a pioneer in promoting adventure playgrounds in the UK, included the above image in her most famous text, Planning for Play, accompanied by the description of the Red Road Flats as ‘a kind of Psychological pollution’.

More recently

Source: G. Laird, Red Road Flats, Balornock (from Petershill Road), CC BY-SA 2.0

In later years Red Road would become ‘notorious’, and was stigmatised in the media as a result of its association with violent crime and suicides. The flats housed a large number of asylum seekers from the 1990s onwards and the resulting tensions became a further focus of media attention. The flats were used as a location in the 2006 film Red Road which arguably drew upon this image of Red Road.

Less was known of the flats early years and the long-term tenants who had lived there for decades. Recently this has been rectified as the flats have received attention from artists and writers and has also been the subject of a Glasgow Museums Exhibition – see www.redroadflats.org.uk. While architectural historians have focused on the story behind the construction of the flats, the work of Chris Leslie, Mitch Miller and Alison Irvine have all drawn on the memories of former tenants to tell the story of what it was really like to live in Red Road over the years.

The stories of former tenants are diverse and show a different side to Red Road that clearly challenges and complicates the image of the flats as portrayed in the local and national media.

Pearl Jephcott’s Homes in High Flats

Regardless of who was to blame for the final demise of the Red Road Flats and the decisions that were made, there are some clues as to possible future problems in the archives of the University of Glasgow where the records of Pearl Jephcott’s ’Homes in High Flats’ research are held. Jephcott was a sociologist based in the Department for Economic and Social Research and her study was to consider ‘some of the human problems involved in multi-storey housing’.

Source: P. Jephcott and H. Robinson, Homes in High Flats, p. 80

In 1968 Jephcott employed a team of market researchers to survey a five percent sample of Glasgow’s high rise tenants. 1,066 questionnaires were completed. She also selected five areas for further study and Red Road was one of these case studies. It was chosen because although it was only two miles north-east of the city centre ‘it was curiously cut off from the main stream of city life’. At this time only two of the eight ‘massive blocks’ (around 31 storeys high) had been occupied but both ‘were already showing signs of social problems since the lifts were proving most inadequate’, and there was also ‘a high proportion of child-users’ (Homes in High Flats, p. 30).

The high numbers of children in these blocks was of particular interest to Jephcott. In noting the lack of services and facilities at Red Road, a poor bus service, only one small shop and expensive mobile vans, no doctors or dentists surgeries, she focuses on the lack of recreational facilities for children. She suggests that with the exception of provision of space for playing football, there were no other facilities for children. No playgrounds with ‘mobile equipment, no pleasant bit of enclosed space for toddlers and very few places for group activites to be held. She stated that ‘in the many visits which the research staff made to the flats at Red road they rarely came away without feeling depressed, particularly at the thought of children being required to grow up there’ (p. 67).

Jephcott’s market researchers completed 26 questionnaires for Red Road. What do these questionnaires tell us about life in the flats in the late 1960s?

In 1968 when Jephcott was completing her survey, only two blocks were occupied at Red Road, 10 Red Road Court (31 floors) and 153/183/213 Petershill Drive (28 floors). There was a mix of people living in these two blocks from older people to young families. One middle aged couple living on the 24th floor in Petershill Drive said there ‘were no children in the block’ in fact they had moved from Barmulloch ‘to get away from so many children’. However there were at least two young families in the block. One young mother living on the 19th floor, who had moved from Springburn, complained that her main problem was the fact that her son ‘wont go out to play’ because he was ‘afraid of the lifts’. She hoped that going to the new play group ‘might bring him out’. She complained about the lifts taking too long to come and often being broken. She also said that there was a lack of shops, the vans ‘were a bit more expensive’ and she had to ‘rush the baby to Springburn for messages’. An old lady living on the same floor complained of the block being ‘a wee bit reserved’ as she ‘never sees a neighbour unless I knock the door and I don’t like to be cheeky. I keep my own counsel’. She commented that ‘there are no children at my end, but the children at the other end are rather wild’. Finally like many other tenants she said that ‘the bus service is terrible and its such a long walk to the bus stop’.

The roots of many problems were there before all the blocks were even completed and occupied in 1969. The isolated location of the scheme and the lack of facilities provided for the residents were problems which persisted throughout the years.

[…] Pearl Jephcott’s 1971 study Homes In High Flats, which surveyed residents across several estates in Glasgow, Scotland, went even further. She found […]