Glasgow Corporation and Le Corbusier – The deputation to Marseilles revisited

Do you have ‘multistorey memories’?

Did you live in high rise flat in Glasgow in the 1960s and 1970s? If so we’d like to hear from you. Please complete our short online questionnaire

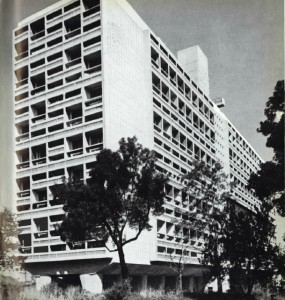

Source: Unité d’Habitation in Marseille (image found at www.brutilismus.com)

As everyone interested in post-war housing, and especially high-rise flats, knows Le Corbusier was extremely influential. His ideas from the interwar years relating to the reconstruction of communities as ‘cities in the sky’ held the imagination of many postwar planners and modernist architects who had to deal with the problems of residential congestion and overcrowding.

In the immediate postwar years Glasgow was the most overcrowded city in the UK (Glasgow had a density of 36.2 persons to the acre. Edinburgh has a comparative density of 13.5 persons per acre, Birmingham 20.19, Leeds 12.7, Liverpool 31.5, Manchester 28.1 and Sheffield 13.15). It was estimated that 60,000 houses were required to adequately house those who required to be cleared from the slums.

One possible solution was to build high.

First, a personal reminiscence. I first heard about Glasgow Corporation’s trip to Marseille when I was studying for my Geography Higher many years ago. My teacher Mr Henderson told us the story of how the Corporation had went off for a ‘jolly’ to Marseilles to look at some flats, came back, started constructing high rise flats built to an Algerian design which ended up infested with terrible damp and then they were demolished.

This is not entirely true, but he was on the right tracks.

Glasgow’s deputation – 1954 not 1947

So when I started researching Glasgow’s relationship with high rise flats last year and found the connection to Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation in Marseille the penny dropped. I began trying to find out if Glasgow Corporation had sent a deputation to view the flats like many other local authorities in the UK and elsewhere in the world. It had in 1947 apparently (according to many websites including Glasgow City Council’s). In fact the block was completed in 1952, work only began in 1947. Eventually I found a reference with the correct date – 1954.

Unfortunately I have been unable to find the official report of the deputation, but I have found details in the Corporation minutes of 1954 and fairly in-depth coverage in the Glasgow Herald of February and March of that year (there are no similar records relating to a trip to Marseilles in 1947).

The Corporation had recently completed work on Crathie Court in 1952 and Moss Heights would be completed that year (1954), both of which were prototype multi-storey constructions in the city using innovative and experimental building methods. So there was a precedent for building higher than four storeys, and the nineteenth century tradition of tenement building had continued in the interwar years in order to ease overcrowding. However Crathie Court was aimed at single women and was comprised of ‘bed-sitting’ flats, Moss Heights were marketed at ‘luxury’ flats. So neither were aimed at housing those in the greatest need – working class ‘slum clearance’ families.

Crathie Court – http://www.hiddenglasgow.com

Moss Heights – http://www.theglasgowstory.com

In 1954 the Corporation was considering how it was going to proceed with large-scale slum clearance in Hutchesontown, Gorbals, Govan and Royston. Multi-storey construction seemed an obvious solution to the problem of rehousing the thousands of people who would be displaced when the over-crowded slum tenements were demolished.

Consequently Glasgow Corporation stated that there were ‘many questions to be investigated in relation to multi-storey development’. In particular concerns relating to the social side of high flats was already being raised by RIBA (Royal Institute of British Architects) and the Central Housing Advisory Committee (See Living in Flats published in 1952), for example, What about gardens? Where will children play? Where will people dry washing? Where will they shop?

On the 13 January 1954 the Corporation agreed to authorise a request from the Housing Convenor, Councillor James R. Duncan and City Architect, Mr A. J. Jury (the man behind Moss Heights), to visit Marseilles ‘for the purpose of inspecting and reporting on the multi-storey development there’. A member of the Planning Committee was to accompany them to this ‘striking example of this type of development’.

Source: Le Corbusier, The Nursery Schools, (Orion Press, New York,1968) p. 23. Image © Lucien Hévre.

The Deputation sets off – 27th February 1954

The Municipal Correspondant of The Herald described the ‘much discussed’ 17-storey block in Marseilles as containing over 300 houses accommodating 1,500 people, and also providing shops and recreational facilities. He notes that the block is also raised on concrete stilts. In 1954 when the deputation visited the building was also described as including a restaurant and shops on the 7th and 8th floors, a doctors house and a school for 150 children of ages four to six on the 17th floor and on the roof was a kindergarten for children aged two to four.

The deputation left for Marseilles on the 27 February 1954 and two days would be spent inspecting the Marseilles flats and consulting with officials. The Herald noted that the study of the Le Corbusier flats would ‘embrace not only the architectural and economic aspects but also the suitability of multi-storey building of this type for the rehousing of families displaced by demolitions in congested city areas’.

Following the inspection of the ‘Flats on Stilts’, as The Herald referred to them on 4 March 1954, James R Duncan described Unité d’Habitation as ‘fascinating’. He told The Herald that the party ‘had all been impressed by the design, but it was too early yet to express any view on the suitability of the flats for Glasgow’. He also stated that they ‘had also acquired details of specifications in printed form’ and that these ‘would require to be translated before their import could be fully appreciated’.

Report to the Corporation – What did James R. Duncan, Housing Convenor and City Architect, Mr A. J. Jury, think of the Unité d’Habitation in Marseilles?

The report to the Corporation was submitted in June, with The Herald describing it as a ‘not proven’ verdict. The report stated that ‘to dismiss the project with the observation that it would be quite unsuitable for Glasgow would be just as wrong as to say that it is perfectly suited to Glasgow’s requirements’. It goes on to say that:

‘the houses are so different from anything that it traditional in Scotland that it is difficult to come to any conclusions on a visit. Only experience of living in them for a period involving at least the different seasons of the year would be reliable’.

One of the main concerns was the difference in Glasgow’s climate to that in Marseilles. As the report stated:

‘the climate is much warmer than ours and, on the occasion of the deputation’s visit, almost summer conditions (Scotland) prevailed. The result was that a coal fire was not missed. Indeed, a coal fire would be scarcely suitable to such a building. It is probably true to say that the building was designed more to keep the dwellings cool in hot weather than to keep them warm in cold weather’.

The building was heated by hot air, very different from the coal fires that were most common in Scotland. The report also described ‘each house’ as being on ‘two floors’ with a balcony ‘forming an open air extension of the living room’. This was a style later known as maisonette flats, not all of which had balconies.

A quarter of the houses in Unité d’Habitation were sold with the remainder rented out. Therefore there was a tenure mix from the beginning. Rents ranged from £1 3s 6d (£28.62 today) a week for one room, kitchen and bathroom to £4 2s 5d (£100.36 today) for the largest flat. Sale values ranged from £1300 to £5200 (approx £32,000 to £127,000 today).

Notably, the deputation’s report argued that

‘the bringing together of 337 families would be regarded as undesirable because it would be assumed that families could never get away from one another’.

Although, it was noted that ‘there was no complaint on that score from the occupiers’ in Marseilles.

Most interestingly, the deputation’s report stated that:‘it would be necessary to ensure that any such block was occupied by a good type of tenant’.

Further it was suggested that while ‘blocks in the style of the “Marseilles block” could in appropriate circumstances provide pleasant living conditions’ they would be ‘very costly’ and ‘would not be suitable for the rehousing of people from slum properties’. Why? The Corporation was either worried about the overall cost of a strategy of ‘building high’ or it was felt that such properties could only be let to ‘good’ tenants, ie the ‘respectable’ skilled working classes, which in turn, excluded those currently living in ‘the slums’.

It was estimated that Unité d’Habitation cost £2 million and the French government, who were responsible for the block, sustained a loss of £2,000 on each house. The deputation’s report stated that it was therefore ‘an experiment’ and ‘any exact repetition could doubtless be carried out at a lower cost’. It was concluded that ‘it does not represent a cheap form of construction or design’.

While the Corporation may have had misgivings about Le Corbusier’s block in Marseilles they did go ahead with a high-rise building drive in the 1960s. Some historians have argued that this was enabled by an increase in government subsidies to encourage high building, others have suggested that Glasgow’s architects and building industry had a tradition of innovation and explorative building methods that enabled high building.

The concerns relating to social conditions and how such multi-storey buildings would fare in the Scottish climate seem to have been swept to one side in the face of the high levels of overcrowding and therefore need for housing for the city’s working classes. Moreover such high blocks were built for the very group that the deputation’s report suggested they were unsuitable for – those who had lived in the slums.

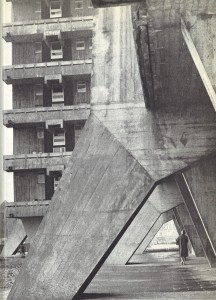

Derivative blocks in Glasgow – Spence’s Hutchesontown C

The most famous blocks to have been directly inspired by le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation in Marseilles was Basil Spence’s Hutchesontown ‘C’ blocks. It too was comprised of maisonette flats with balconies. It also famously took longer to build and cost more than expected.

Source: P. Jephcott and H. Robinson, Homes in High Flats, (Oliver & Boyd: Edinburgh), 1971, Plate 16

The job architect, Charles Robertson, stated in 1992 that Spence’s brief was to build three slab blocks (all quotes from Miles Glendinning (ed.) Rebuilding Scotland: The Postwar Vision 1945-1975 (Edinburgh: Tuckwell Press, 1992)). He was required to build 400 individual dwellings, of five different types. Lifts were to stop on alternate floors in order to be more ‘economic’ – hence the reason why the houses were maisonettes. Robertson describes the slabs as being ‘composed, in effect, of ten individual “towers’ each 40 feet square’. They were linked by communal balconies or ‘garden slabs’. These balconies were seen as ‘a perpetuation of the green’ and as ‘a space for some tubs of flowers, and to hang out the washing, to give the baby an airing, and to provide a garden fence to gossip over’. Like Unité d’Habitation Spence’s blocks were also on stilts, which was supposed to allow the space under the building to be used by the community. However what the Spence blocks lacked were the recreation, shopping and educational facilities which Le Corbusier’s block had.

Robertson, reflecting on the state of the building in 1992 suggested that the concrete ‘had not weathered at all well’ and had ‘deteriorated in many places’ with the reinforcing being ‘exposed in several places’. He admits that the building had ‘not been popular’ and crucially had not been maintained for twenty years. As he states:

‘what we did not realise when we were building things of this nature is that they involve a very high maintenance cost. And that cost was impossible for the local authority to deal with’.

Hutchesontown ‘C’ was demolished in 1993.

Another section of the Hutchesontown Comprehensive Redevelopment Area, Hutchesontown ‘E’, was built to an Algerian design and was demolished in 1987 after years of complaints from tenants as to the damp problem. I think this must be why my teacher Mr Henderson made the connection with Algeria.

Which brings us nicely to one of the main aims of this project – to revisit and reassess the many popular narratives that circulate concerning high rise flats in Glasgow. Everyone has a story, everyone knows someone who lived in or still does live in a high flat. Everyone has an opinion on why they were built.

There is a partial architectural history and political history of Glasgow’s postwar housing policy but no one has asked those who lived in them to give their story. We want to hear those stories!

If you have ‘multistorey memories’ please get in touch –

You can email us directly at multistoreymemories@gmail.com

Facebook ‘Multistorey Memories Glasgow’

Twitter @multimemories

Alternatively you can follow the link and complete our short questionnaire