Did you live in a high flat in Glasgow in the 1960s and 1970s? Where did you play?

We’d love to hear from you!

You could fill out our short questionnaire

Or You can leave a comment under this post, email us or look us up on social media:

Email: multistoreymemories@gmail.com

Website: www.glasgow.ac.uk/housingandwellbeing

Facebook: ‘Multistorey Memories Glasgow’

Twitter: @multimemories

Le Corbursier’s vision

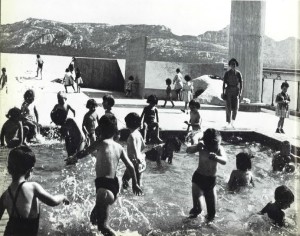

When Le Corbusier envisaged the high rise building as a self contained community he made provision for communal facilities such as restaurants, health centres and crucially a nursery and school for children. There was (and still is) even a paddling pool on the roof.

Source: ©By Crookesmoor (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

The problem of housing children in high rise flats had been raised from the early 1950s. It was discussed in a 1955 symposium organised by the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) where the author of the government’s Living in Flats of 1952, Margaret Willis, outlined the many drawbacks of flat living. The main problems were lack of space for play inside the flat, young children under five being stuck in and not getting out to play, as well as lack of play facilities for both the under fives and for those children who could go out to play on their own. Basically Willis suggested that families with young children should not be housed in high flats. Many commentators echoed such comments over the preceding years. This did not stop Glasgow City Council from building high blocks all over the city which included three and four apartment flats for families (the same is true of large city councils the length and breadth of the UK).

Le Corbusier had suggested that in the Unité d’habitation:

‘we are setting up an extraordinary network of services for raising children, extending from infancy to adolescence … This youth will be king of its own household’

(Le Corbusier, 1968, as quoted in Kozlovsky, The Architecture of Childhood, p. 198). As Kozlowsky argues, the needs of children were central to the design of the Unité (p. 201).

This was not the case in the derivative high rise blocks of housing built by the Corporation in Glasgow and elsewhere. As a result high rise flats continued to provoke criticism on the grounds that they were not suitable for children.

In response Le Corbusier published The Nursery Schools in 1968. This book is a defence of his architecture where he states that a ‘five years war’ had been ‘waged against us’; ‘A cruel and perfidious war, anonymous , relentless’. He criticises suburbia and high rise buildings which do not include ‘the common services, shops, sports facilities, schools, garages, avenues, etc.’ that he himself included in the Unité (Corbusier, p. 14-17).

Kozlovsky suggests that while the Unite d’Habitation gave rise to ‘The New Brutalism’, a monumentalist architectural style, the emphasis placed on this building as ‘an aesthetic turning point’ has resulted in many accounts of the building ignoring ‘its many child centred features’ (Koslovsky, p. 198)

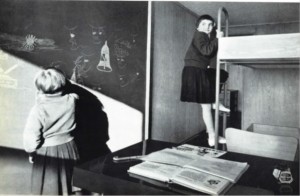

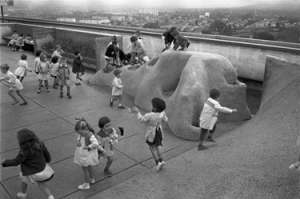

In The Nursery Schools photographs show children operating lifts, the children’s rooms which can be divided with moving panels (affixed with blackboards for drawing on), children playing on the balconies adjoined to their rooms, children playing in the ‘safe’ alternative to the street below by a busy road – the roof, which also housed the nursery school. There were many community activities on the roof including the annual summer fair, with the end of school celebration being held there too.

Source: ‘Here are the kids in their own realm – those much talked about rooms just 6ft wide’, Le Corbusier, The Nursery Schools (New York: Orion Press) 1968, p. 49. Photo credit: ©Lucien Hervé, Paris

Source: ‘Before she went to bed there was still something this little girl wanted to say on her blackboard’, Le Corbusier, The Nursery Schools (New York: Orion Press) 1968, p. 52. Photo credit: ©Lucien Hervé, Paris

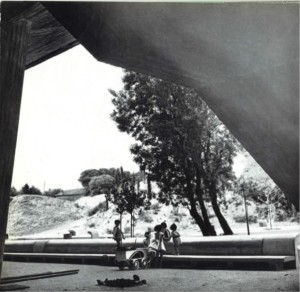

Source: ‘This is the territory of the Nursery School’, Le Corbusier, The Nursery Schools (New York: Orion Press) 1968, p. 32. Photo credit: ©Lucien Hervé, Paris

In the background of this photo you can see the famous inclined wall that children played on. Le Corbusier criticises the ‘Mr NOs’ of the world who said ‘I tell you, they’re going to kill themselves’. His response ‘Of course not, you old fuddy-duddies!’.

More photos (widely available online):

Spence’s interpretation

The publication of The Nursery Schools came too late for the children living in high rise flats in Glasgow. The Corporation had not included such facilities via their in-house architects or the architects at Wimpey, who built high flats throughout the city.

Even the star architects of the day, working in Glasgow’s largest Comprehensive Development Area (CDA) in the Gorbals, Sir Robert Mathew, who designed Hutchesontown B and Sir Basil Spence, Hutchesontown C (Queen Elizabeth Square) also neglected to make children central to their designs. Sir Basil Spence had obviously been influenced by Le Corbusier’s ‘brutalist’ architecture. However, Marjorie Allen of Hurtwood, a pioneer in promoting adventure playgrounds in the UK in the postwar years, was an early critic of Spence’s design for the Gorbals. While The Times’ special correspondent had described the architects’ plans as ‘one of the most progressive social and architectural experiments this country has seen’, Allen was not happy that ‘no mention’ was made ‘of playgrounds or open-air nursery schools’. She asks

‘where will the highly adventurous and noisy children, from three years to 18, find their vital space to play and work?’

(The Times, 29 August 1958, p. 9).

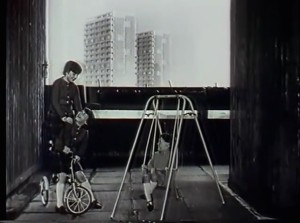

In response Sir Basil suggested that

‘the whole of the underside of the tall block is planned as a covered paved play place, as cover is essential in Scotland where children like to play near their homes’

(The Times, 30 August 1958, p. 7).

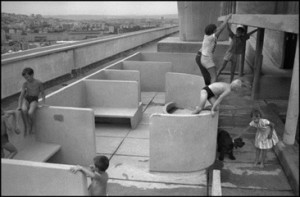

Source: University of Glasgow archives, DC 127/22, ‘Homes in High Flats’ collection

Source: University of Glasgow archives, DC 127/22, ‘Homes in High Flats’ collection

A sort of paddling pool was included under the block, though this was later filled in. As far as I can tell from photographs taken under the blocks there were no other provisions made for children’s play. Although, as Nicholas Taylor argued in an article entitled ‘The Failure of ‘Housing’ in the Architectural Review of November 1967 ‘children of all ages run wild in the undefined wastes known to the faithful as pilotis’ (p. 348).

Nevetheless, maybe this was not quite the same as under the Unité in Marseilles?

Obviously the weather in Marseilles was better, but was there the same wind tunnel under the building?

Source: ‘3 hectares of grass and trees, for playing and strolling, and guaranteeing everyone sun, space and greenery’. Le Corbusier, The Nursery Schools (New York: Orion Press) 1968, p. 26. Photo credit: ©Lucien Hervé, Paris

In just about all the high flats in Glasgow, children could play on the verandah, (Spence’s ‘hanging gardens’ in Queen Elizabeth were particularly big) but perhaps this is not quite the same as a balcony in the South of France , not to mention the sun terrace and nursery on the roof?

Source: Still from ‘High Rise and Fall’ a 1993 documentary on the demolition of Queen Elizabeth Square – http://dirtymodernscoundrel.blogspot.co.uk/2015/07/rip-queen-elizabeth-square.html

Source: ‘Balcony of a child’s bedroom. Notice that it hasn’t been put there accidentally. It is one of the biological elements making up each child’s bedroom in the Unite d’Habitation’, Le Corbusier, The Nursery Schools (New York: Orion Press) 1968, p. 51. Photo credit: ©Lucien Hervé, Paris.

Did you grow up in Spence’s Queen Elizabeth Square? Where did you play?

We’d love to hear from you!

You could fill out our short questionnaire

Or You can leave a comment under this post, email us or look us up on social media:

Email: multistoreymemories@gmail.com

Website: www.glasgow.ac.uk/housingandwellbeing

Facebook: ‘Multistorey Memories Glasgow’

Twitter: @multimemories