Did you live in a high flat in Glasgow in the 1960s and 1970s? Where did you play?

We’d love to hear from you!

You could fill out our short online questionnaire

Or You can leave a comment under this post, email us or look us up on social media:

Email: multistoreymemories@gmail.com

Website: www.glasgow.ac.uk/housingandwellbeing

Facebook: ‘Multistorey Memories Glasgow’

Twitter: @multimemories

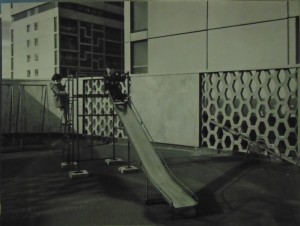

Source: Playground at Hutchesontown, 1960s, University of Glasgow Archive, DC 127 Homes in High Flats collection

If, as discussed in Part 1, Le Corbusier did not influence architects, construction companies and City Corporations/Councils to incorporate child-centred facilities in to high rise housing in the UK, the question is what provisions were made and where did children play?

Playing inside

Well, inside the blocks there were few facilities, if any at all, provided for children’s play when the flats were first constructed. So if it was rainy children played in the halls, lifts and entrance halls. This was obviously noisy and many neighbours didn’t like it, not to mention the caretakers.

In his critique of the Spence blocks at Queen Elizabeth Square in Architectual Review (November 1967), Nicholas Taylor states that ‘there can be few signs meaner or more pathetic than children of four or five finding what room they can in the upper lift halls as a playground’ (p. 348).

Although I’ve heard from former residents that they loved playing in the halls at Queen Elizabeth Square where the kids held their own art exhibitions and concerts – with some floors being more welcoming than others.

Source: Queen Elizabeth Square, University of Glasgow Archive, DC 127 Homes in High Flats collection

Source: Still from ‘High Rise and Fall’ a 1993 documentary on the demolition of Queen Elizabeth Square – http://dirtymodernscoundrel.blogspot.co.uk/2015/07/rip-queen-elizabeth-square.html

Children also played on the balconies or verandahs but some mums worried about how safe this was. In Queen Elizabeth Square, I’ve been told that kids used to sit up (or even walk along) on the concrete wall of the verandah as there was a wee ledge. However as Part 1 showed, the balconies at Queen Elizabeth Square were big enough for riding bikes, playing football and all sorts of other games. Some people even had wee huts for the kids to play in.

Later, in the late 1960s and 1970s, as it became increasingly clear that local authorities were not going to provide facilities, or didn’t have the money or resources, attempts were made by groups of mothers, sometimes with the help of the PreSchool Playgroups Association, to use community rooms in high rise blocks for play groups for the under fives. Pearl Jephcott and her research team also tried to help some young mothers in Royston to establish a play group in Charles Street High Flats which was eventually taken over by the Save the Children Fund. I’ve also been told about community run facilities for children and young people in high rise blocks.

See Castlemilk History’s photos of the Bogany mum’s and toddlers dressed up for the Castlemilk Fair

What about outdoor facilities?

During post-war reconstruction there was a renewed emphasis on the need for children to have designated space within the city that was theirs. The role of the child in the city was changing. Streets were no longer considered a safe place to play. The solution was specially designed play grounds to cater for children of different ages. Here children could avoid traffic. As car ownership grew in the postwar years so too did road traffic accidents and incidence of injury and fatalities.

However, not all of these playgrounds were simply swings, chutes and roundabouts like this one:

Source: Playground at Hutchesontown D, 1960s, University of Glasgow Archive, DC 127 Homes in High Flats collection

It would appear that perhaps Le Corbusier’s ‘New Brutalist’ aesthetic influenced the design of playgrounds built in post war housing estates in the UK.

In Glasgow many of the post-war playgrounds included ‘architectural’ concrete stepping stones (more accurately attributed to Aldo van Eyck), tunnels and metal climbing frames (perhaps the latter is not entirely brutalist?)

Here’s some photographs I took recently at the high flats at Broomhill. It looks like the play spaces haven’t changed much since construction in the mid 1960s:

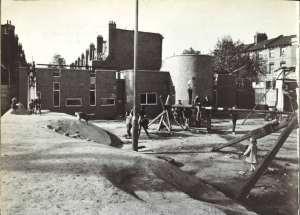

Similar styles of playground could be found in the Gorbals and elsewhere. The playground in the following photo was referred to by the kids that played in it as ‘the jumps’ and it is well remembered by those that played there.

Source: Hutchesontown, May 1958 ©Virtual Mitchell

As discussed in Part 1, children could also play around the bl

Adventure Playgrounds

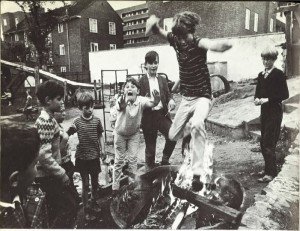

The Gorbals also had an Adventure Playground. Adventure or ‘Junk’ Playgrounds were first established after the Second World War, often on bombed sites in inner cities. The movement began in Denmark, and Lady Marjorie Allen is credited with bringing adventure playgrounds to the UK when she established the first in London.

Source: ‘St John’s Wood Adventure Playground, London’, Lady Allen of Hurtwood, Planning for Play (London: Thames and Hudson, 1968), p. 60. © John Drysdale, Camera Press Ltd, London

Source: ‘Notting Hill Adventure Playground, London’, Lady Allen of Hurtwood, Planning for Play (London: Thames and Hudson, 1968), p. 64. © Colin Westwood, FIIP, FRPS

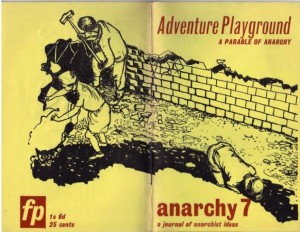

The principles were to let children do what they wanted. They could built huts from wood, could dig in the dirt, play whatever games they liked. There was a play leader but he/she did not guide activity, but supported the play activities of the children. Colin Ward was also a proponent of Adventure Playgrounds as illustrated in this issue of Anarchy

The ‘Vennie’ in the Gorbals (affectionately remembered on facebook) was run by folk singer Matt McGinn, who said:

‘My job here is not to tell the kids to do this or do that, but to be there if they want help. Another important, if unofficial job, is to give them lights for their fags’

Source: ‘Venny kids had a swinging time’, Evening Times, 26 June 2014